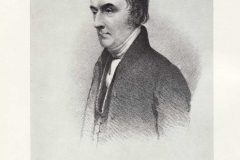

Samuel Tuke (31 July 1784 – 14 October 1857) was born in York, England.

He greatly advanced the cause of the amelioration of the condition of the insane, and devoted himself largely to the York Retreat. The methods of treatment pursued there were made more widely known by his Description of the Retreat near York. In this work Samuel Tuke referred to the Retreat’s methods as moral treatment, borrowed from the French “traitement moral” being used to describe the work of Pussin and Pinel in France (and in the original French referring more to morale in the sense of the emotions and self-esteem, rather than rights and wrongs). Samuel Tuke also published Practical Hints on the Construction and Economy of Pauper Lunatic Asylums (1815).

Samuel was part of a Quaker family. He was the son of Henry Tuke and the grandson of William Tuke, who founded the York Retreat. Samuel Tuke’s two sons James Hack Tuke and Daniel Hack Tuke were also active in humanitarian concerns.

The Retreat still provides mental healthcare for the population of York and the wider community. Samuel Tuke can be found buried in the Quaker cemetery within the hospital grounds.

About The Retreat

The Retreat occupies a central place in the history of psychiatry. Every textbook on the subject mentions the unique part played by it in the reshaping of attitudes towards people who are mentally ill.

Opened in 1796 by William Tuke, a retired tea merchant, the original Retreat was intended to be a place where members of The Society of Friends (Quakers) who were experiencing mental distress could come and recover in an environment that would be both familiar and sympathetic to their needs. Some years earlier, a Leeds Quaker, Hannah Mills, had died in the squalid and inhumane conditions that then prevailed in the York Asylum, and appalled at this, Tuke and his family vowed that never again should any Quaker be forced to endure such treatment.

The Retreat was based on the Quaker belief that there is ‘that of God’ in every person, regardless of any mental or emotional disturbance. Although to many modern-day mental health practitioners this might seem a reasonable baseline assumption to make, at the time it was a revolutionary departure from the norm.

Moral Treatment at The Retreat

The original Retreat of 1796 did not set out to invent any new model of treatment for people who were mentally ill. It was merely intended to be a supportive and healing environment, based on Quaker principles. Over time, however, The Retreat opened its doors to an increasing number of non-Quaker visitors and residents, and its regime and methods became the subject of general interest to those concerned with mental health care, both in Britain and abroad. This interest led William Tuke’s grandson Samuel, in 1813, in his book Description of The Retreat to explain and encapsulate The Retreat’s methods and philosophy as “moral treatment”.

Samuel Tuke borrowed the term “moral treatment” from the term “traitement moral” which was used to describe the work of Pinel, a French revolutionary famous for his liberation of mental asylum inmates in Paris at about the same time as The Retreat’s founding. The original French form “moral treatment” referred more to treatment of the morale, in the sense of the emotions and the self-esteem, rather than the sense of “rights and wrong” that we tend to associate with the word “moral”. This has led to some unfortunate misunderstanding about the term.

Samuel Tuke himself laid great emphasis on the importance of improvement of morale for people in distress, and this was to be achieved by a combination of environmental and practical considerations.

Moral treatment may have had its flaws and its critics but, viewed in its historical context, as an alternative to the established treatments of the day, it was quite revolutionary. Within a short period of time after The Retreat had been established, others were inspired to try treating patients along similar lines.

The Retreat itself became influenced by the emerging discipline of psychiatry and assumed an increasing degree of medical emphasis, although it always retained its reputation for compassion and respect for the people it treated.

The Retreat today

The present day Retreat seeks to retain the original principles behind the early moral treatment practised here, whilst being responsive to what is best in latest clinical expertise and practice.

http://www.theretreatyork.org.uk/

*Link On The Front Page.*

William Tuke (1732 – 1822)

A leading Quaker philanthropist, William Tuke introduced new, more humane, methods of caring for the mentally ill.

William Tuke was born in York on 24 March 1732, into a leading Quaker family. He entered the family tea and coffee merchant business at an early age. Alongside his commercial responsibilities, he was able to devote much time to the pursuit of philanthropy.

When a Quaker died in the squalid and inhumane conditions of the York Asylum, Tuke was invited to visit and was appalled by what he saw there. In the spring of 1792, he appealed to the Society of Friends (as the Quakers were also known) to revolutionise the treatment of the insane. He collected sufficient funds to open the York Retreat for the care of the insane in 1796. This was the first of its kind in England, and pioneered new, more humane, methods of treatment of the mentally ill. These included removing inmates’ chains, housing them in a pleasant environment, with decent food and adopting a programme involving the therapeutic use of occupational tasks. Tuke’s work was contemporary with similar groundbreaking work in France by Philippe Pinel, although the two acted independently of each other.

William Tuke died in 1822. At least four members of his family also pursued related philanthropic work. His son Henry (1755 – 1814) was a co-founder of the York Retreat. Henry’s son Samuel (1784 – 1857) carried on with his own interest in the condition of the insane. He wrote an account in 1813 of the York Retreat ‘Description of the Retreat’ containing a report on the principles of ‘moral therapy’, which were considered to be the basis of the therapeutic environment there. Written at the request of his father, the work focused on the abuses common in the madhouses of the time, and gave direction to the urgent need for reform.

Samuel’s son James Hack Tuke (1819 – 1896) in his turn aided in the management of the York Retreat and later focused on famine relief aid to Ireland. James’s brother Daniel Hack Tuke (1827 – 1895) co-wrote the important treatise ‘A Manual of Psychological Medicine’ in 1858 and became a leading physician dedicated to the study of insanity.

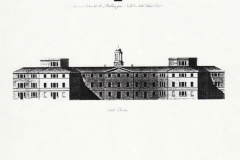

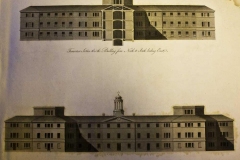

The influence of The Retreat is seen in the advice given by Samuel Tuke to the West Riding magistrates when the design of the asylum was being contemplated, which was based on some 20 years’ experience of the Retreat. His advice was accepted by them and he was invited to instruct the architects and supervise their work. In 1819 his “ Hints on the Construction and Economy of Pauper Lunatic Asylums” ( written specifically with the Wakefield Asylum in mind) was printed and published, along with the architect’s drawings and plans.

York Asylum – Now Bootham Park.

Parliamentary Papers 1814/15 Vol IV

11th July 1815 Madhouses in England Report No 296

Minutes of Evidence pp 809-

First Report of Minutes pp 001-130

Note :- This is a report on the York Lunatic Asylum, not to be confused with The Retreat which was run by the Quakers.

Godfrey Higgins esq Magistrate W Riding pp 001 811 Ist of May 1815 Rt Hon George Rose in the Chair.

Where do you live ?

At Skellow Grange near Doncaster in Yorkshire

You are a Governor of the York Asylum and a Magistrate of the West Riding of Yorkshire ?

I am.

Have you any knowledge of the state and condition of the York Lunatic Asylum, and the method of treatment of the patients in that Asylum ?

I have.

Have the goodness to state to the Committee, how you became possessed of that information ?

In the year 1813 application was made to me to grant a warrant against a man who had assaulted a poor woman; upon enquiry I found the man to be insane, and ordered him to be sent to the Asylum at York: Sometime afterwards he returned, and I was informed he had been extremely ill-used; (the name of the man was William Vickers;) in consequence of this I published several letters and other documents, upon which various meeting of the Governors were held from time to time for the course of 12 months, until the 27th of August last; upon which day all the servants and officers of the house were dismissed, or their places deemed vacant, except one. Not being perfectly satisfied with what was done, I thought it incumbent upon me to publish a letter to Lord Fitzwilliam, as Lord Lieutenant of that Riding, in which to the best of my knowledge I stated every thing that I knew relating to the Institution and to the abuses which had taken place in that house.

The Appendix contains a Report of the Committee appointed to investigate the abuses, and the New Rules and Regulations.

In what condition did you find the Asylum when you visited it in the Spring Assize week of 1814 ?

Having suspicions in my mind that there were some parts of the Asylum which had not been seen, I went early in the morning determined to examine every place; after ordering a great number of doors to be opened, I came to one which was in a retired situation in the kitchen apartments, and which was almost hid by the opening of a door in the passage; I ordered this door to be opened; the keepers hesitated, and said the apartment belonged to the women, and they had not the key; I ordered them to get the key, but it was said it was mislaid, and could not be found at the moment; upon this I grew angry, and told them, I insisted upon its being found, and that if they would not find it, I could find a key at the kitchen fire-side, namely, the poker; upon that the key was immediately brought. When the door was opened, I went into the passage and found four cells, I think, of about eight feet square, in a very horrid and filthy situation, the straw appeared to be almost saturated with urine and excrement; there was some bedding laid upon the straw in one cell, in the others only loose straw; a man (a keeper) was in the passage doing something, but what I do not know; the walls were daubed with excrement; the air holes, of which there was one in each cell, were partly filled with it; in one cell there were two pewter chamber pots loose. I asked the keeper if these cells were inhabited by the patients ? he told me they were at night. I then desired him to take me up stairs and shew me the place of the women who came out of those cells that morning. I then went up stairs, and he shewed me into a room which I caused him to measure, and the size of which he told me was 12 feet by 7 feet and 10 inches, and in there were 13 women, who he told me had all come out of those cells that morning.

Were they pauper women ?

I do not know; I was afraid that afterwards he should deny that, and therefore I went in and said to him “Now Sir, clap your hand upon the head of this woman” and I did so too; and I said “Is this one of the very women that were in those cells last night” and he said she was; I became very sick, and could not remain longer in the room, I vomited. In the course of an hour and a half after this, I procured Col Cooke of Owston and John Cooke esq of Camps Mount, to examine those cells; they had come to attend a special meeting which I had caused to be called that day at 12 o’clock; whilst I was standing at the door of the cells waiting for the key, a young woman ran past me, amongst the men servants, decently dressed; I asked who she was, and was told by Atkinson, that she was a female patient of respectable connections. At the special meeting of the Governors which I had caused to be called, I told them what I had seen, and asked Atkinson, the apothecary, in their presence, if what I had said was not correctly true; and I told him, if he intended to deny any part of it, he must do it then, he bowed his assent, and acknowledged what I said was true. I then desired the Governors to come with me to see those cells; and then I discovered, for the first time that the cells were unknown to the Governors; several of the Committee, which consisted of fifteen, told me they had never seen them, that they had gone round the house with His Grace the Archbishop of York, that they had understood that they were to see the whole house, and these cells had not been shewn to them. We went through the cells, and at that time they had been cleaned as much as they could be in so short a space of time. I turned up the straw in one of them with my umbrella, and pointed out to the gentlemen, the chain and handcuff which were then concealed beneath the straw, and which I then perceived had been fixed onto a board newly put down in the floor. I afterwards enquired of one of the Committee of five, who had been appointed to afford any temporary accommodations which they could find for a moderate sum of money to the patients, if those cells had been shewn to that committee, and I was told they had not.

Before I saw these cells, I had been repeatedly told by Atkinson the apothecary, and the keepers, that I had seen the whole house that was occupied by patients; I afterwards was told by a professional man, Mr Pritchett, That he had heard Mr Watson the architect, ask one of the keepers what those places were; Mr Watson was at that time looking out of the staircase window, and he heard the keeper answer Mr Watson that they were cellars and other little offices. The day after my examination of these cells, I went again early in the morning to examine them, after I knew that the straw could have been used only one night; and I can positively say, from this examination that the straw which I first found there must have been in use a very considerable time. Early in the investigation which took place into this Institution, several gentlemen came forward to state, that they had examined the house on purpose to form a judgement of it, but though several of them were present when I stated the case of these cells, they did not state that they had seen them. When Colonel Cooke of Owston, was n one of the cells, he tried to make marks or letters in the excrement remaining upon the floor after it had been cleaned and fresh straw put into it, which he did without any difficulty, and which he will be ready to state to the Committee if required. The day after I saw these cells, I went up to the apartments of the upper class of female patients, with one of those men keepers as I should suppose to be about thirty years of age, one of those who were dismissed in August; and I asked him, when at the door of the ward, if his key would not open those doors; I did not give him time to answer, but I seized the key from his hand, and with it opened the outer door of the ward, and then went and opened the bed-room doors of the upper class of female patients, and locked them again; I then gave him his key again. Mr Samuel Tuke, a Quaker, of York was standing by and saw me.

Source: Asylums in Yorkshire

From Alan Longbottom at Pudsey.

http://www.institutions.org.uk/asylums/england/YKS/yorkshire_asylums.htm